I’m not sure how much fun a guy is allowed to have, but I about maxed out the meter earlier this week in Reston, Virginia where I was invited to give a lecture on ‘‘The Beats.”

Giving the talk to the enthusiastic salon audience was super-delightful, but even more fun was the outstanding Q&A that followed. The number and quality of thought-provoking questions and comments was gratifying and informative. One thing of import I learned is to communicate the difference between “Beats” and “Beatniks.”

The Beats were not Beatniks—in fact they found the term insulting.

The backstory:

The Beats entered the national consciousness in the mid-1950s, but the name has its genesis in the 1940s beginning with a character from Chicago named Herbert Huencke.

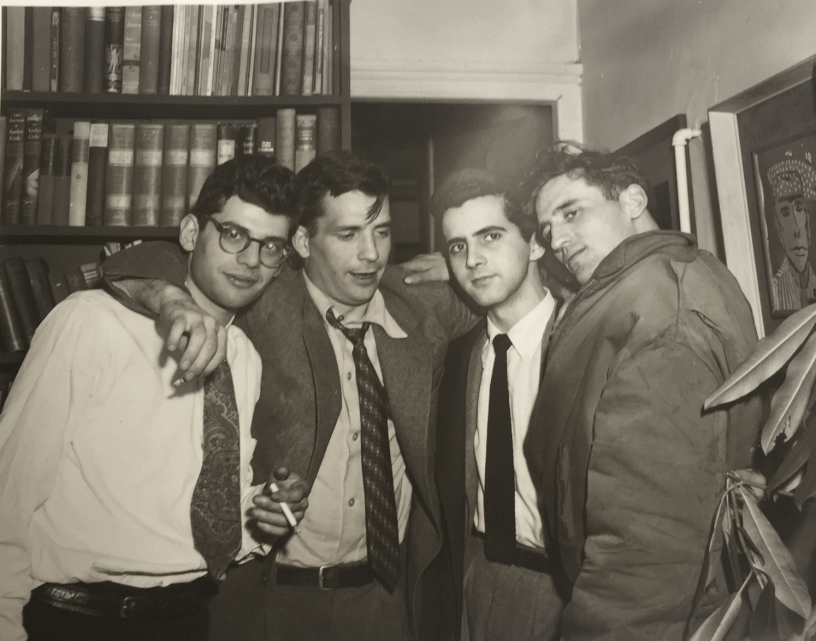

Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs, unpublished wannabe writers, were friends and lived near Columbia University when Huencke arrived in 1945.

In the underworld of Chicago “beat” meant robbed or cheated. Huencke introduced the word to Kerouac but never expected it to get the traction, or definition, that followed.

In 1948 Kerouac was speaking with writer John Clellon Holmes and used the phrase “you might say we are a beat generation.”

In 1952, Holmes in a New York Times Magazine piece wrote “This is a Beat generation. It involves a sort of nakedness of mind, and ultimately, of soul, a feeling of being reduced to the bedrock of consciousness.”

It was also in the early 50s when Kerouac began to emphasize beatitude, and beatific, quality of Beat. Ginsberg wrote about Kerouac’s take on “beat,” explaining it’s “where you are actually beat to a point where you can see the world in a visionary way, which is the old classical understanding of what happens in the dark night of the soul.”

Kerouac himself spelled it out in 1957 in the October 4 issue of Saturday Review: His book On the Road had been released a month earlier and he and the Beats were suddenly cast into the national spotlight. In the interview he said, “I guess I was the one who named us the ‘Beat Generation.’ This includes anyone from fifteen to fifty-five who digs everything, man. We’re not Bohemians, remember. Beat means beatitude, not beat up. You feel this. You feel it in jazz, real cool jazz, or a good, gutty, rock number. The Beat Generation loves everything, man. We go around digging everything. Everything means something; everything’s a symbol. We’re mystics. No question about it. Mystics.”

Something else happened October 4, 1957 – the same date of the Saturday Review piece—the Russians launched the satellite “Sputnik.”

The following month Herb Caen, columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, merged the two words, Beat and Sputnik, coining the term “Beatnik.” It was the first time the word appeared in print, and it caught fire, becoming part of the national lexicon and to this day continues to be confused with “Beats.” The inference was that the Beats were far-out space-brained Communists.

The same day Caen’s piece appeared in the paper, Kerouac ran into him. In 1995 Caen recalled: “I ran into Kerouac that night at El Matador. He was mad. He said, ‘You’re putting us down and making us sound like jerks. I hate it. Stop using it.’”

The Beats were not Beatniks, they were Post-World War II American writers, and if their stories and lives interest you, as they do me, you might subscribe (free) to my Substack Beat Moments.