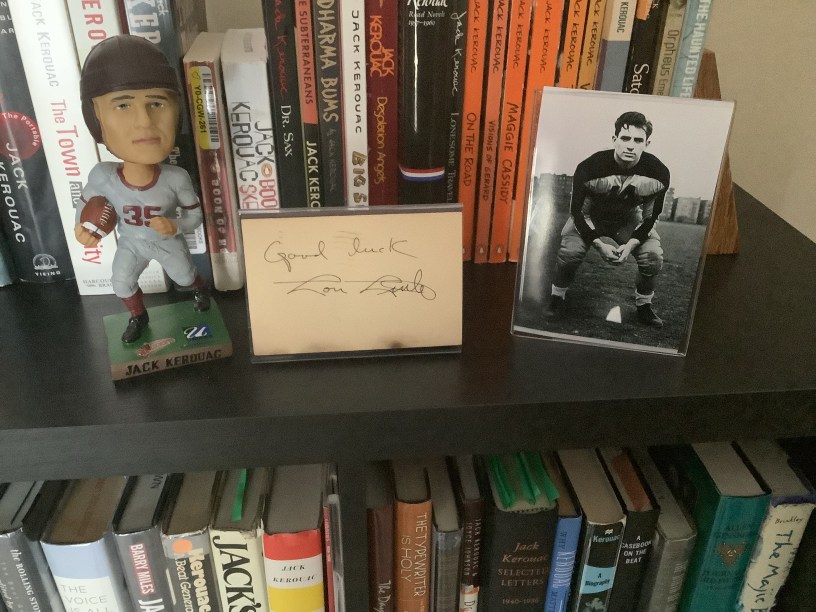

Jack Kerouac’s Football Odyssey

by James K. Hanna

Part I

One aspect of his life that often gets lost, at least in my experience, when people talk about Jack Kerouac, is his love of football. As youngster and young adult, he was an outstanding athlete. As a teenager he excelled at baseball and track, but his first love was the gridiron.

The affair began in 1935 as a twelve-year-old playing sandlot ball in his hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts and ended in disappointment at Columbia University in 1942.

In the years between the sandlot and Columbia’s Baker Field he was a standout gridder for Lowell High School, 1938, and the following season at Horace Mann Prep School, which he attended for one year before enrolling at Columbia in the fall of 1940.

Already an inveterate diarist, he intended to chronicle his activities and thoughts throughout his freshman year at Columbia in a typewritten journal he titled “The Journal of an Egotist.” He gave up on the project but not before writing, “When I was about 12 years old, I was perhaps the best little sandlot ballcarrier for miles around. Today, thanks to that, I am receiving financial assistance through a great University…a University so great that it would not give me financial assistance unless I possessed good marks in school [and] a good indication of intelligence. I had both, at least the former, and here I am, cocked and crowing to the world!” [i]

Two years later, on October 17, 1942, as the nationally ranked Army cadets defeated Columbia at Baker Field 34-6, Kerouac wore a football uniform for the last time. It was the day that, as he wrote, he “gave up rock-ribbing football to turn to Wolfean novels.” [ii]

It was the end of an eight-year love affair with the game. The twenty-year old’s fondness for the gridiron that began at age twelve playing sandlot football for the Dracut Tigers, his neighborhood team included of twelve to fifteen-year-olds, came to a crashing halt.

He recorded memories of his football days in Vanity of Duluoz, subtitled An Adventurous Education, 1935-46, published in 1968, the year of his death. He wrote, “All footballers know that the best football players started on sandlots.” [iii]

Dracut’s sandlot was an up-and-down uneven field with no goalposts, measured off for 100 yards more or less by a pine tree on one end and a peg on the other. [iv]

His athleticism was on full display beginning in his first game, on a Saturday morning in October of 1935, when he scored nine touchdowns as his Tigers beat the Rosemont Tigers, 60-0. “I was probably the youngest player on the field. I was also the only big one in the sense of football bigness, thick legs and heavy body.” [vi]

Other sandlot games were played at the Bartlett Junior High School field and in a cow field near St. Rita’s Church.

Sandlot games prepared him for his glory days at Lowell High School.

Part II

When Kerouac advanced from the sandlot games to the Lowell High School team, academic ambition was added to his love of the game,

“because I wanted to go to college and somehow knew my father would never be able to afford the tuition, as it turned out to be true. I, of all things, wanted to end up on a campus somewhere smoking a pipe, with a button-down sweater, like Bing Crosby, serenading a coed in the moonlight down the old Ox Road as the strains of alma mater song come from the frat house. This was our dream gleaned from going to the Rialto Theater and seeing movies. The further dream was to graduate college and become a big insurance salesman wearing a gray felt hat getting off the train in Chicago with briefcase and being embraced by a blond wife on the platform, in the smoke and sot of the bigcity hum and excitement. Can you picture what this would be like today? What with air pollution and all, and the ulcers of the executive, and the ads in Time Magazine, and our nowadays highways with cars zipping along by the millions in all directions in and around rotaries from one ulceration of the joy of the spirit to the other? And then I pictured myself, college grad, insurance success, growing old with my wife in a paneled house where hang my moose heads from successful Labradorian hunting expeditions and as I’m sipping bourbon from my liquor cabinet with white hair I bless my son to the next mess of sheer attack (as I see it now).

“As we binged and banged in the dusty fields we didn’t even dream we’d all end up in World War II, some of us killed, some of us wounded, the rest of us eviscerated of the 1930s innocent ambition. ”[vii]

In Vanity of Duluoz he focused on his senior year at Lowell, claiming that as an underclassman the coach thought he was too young to play regularly.

As a sixteen-year-old-senior, wearing number 35, he started the first game of the season versus Greenfield, won 26-0 by Lowell, but saw limited play the following week in an 18-0 victory over Gardner, Massachusetts. In the third game, versus Worcester Classical his prowess was on display as he ran back a punt 64 yards for a touchdown and scored two ore with runs of 25 yards each.

The “big test came for Lowell,” in the fourth week versus Manchester. Kerouac did not start, though the students in the stands started the chant, “We want Kerouac! We want Kerouac!” He carried the ball only once, late in the game, but Lowell won its fourth in a row, 20-0.

Even the Lowell newspaper reported “the crowd wanted Jack Kerouac and got him late in the fourth quarter.”[viii]

In the fifth game of the 1938 season, he scored two touchdowns for the Red and Grey squad in a 43-0 victory over Keith Academy. It was this game, according to Kerouac, that he drew the attention of major college recruiters, including Frank Leahy, coach at Boston College. (Leahy would go on to coach Notre Dame, 1941-1943, 1946-1953).

The sixth game versus Malden resulted in a scoreless tie, with Kerouac seeing little action. “This afternoon made no difference whether I carried the ball, or started, or played juts a quarter or not; it was a defensive pingpong blong of a game; dull enough but watched by interested observers.”

This game was followed by a loss at New Britain, Connecticut.

The following game, versus Nashua, was, in Kerouac’s words, “the toughest game of football I ever played” and “the most beautiful and most significant.” It was this game where Kerouac’s talents were noticed by Columbia Coach Lou Little, who would compete with Leahy to attract Jack to college. Though Nashua won, 19-13, Jack ran for 130 yards, and scored both Lowell touchdowns, with a 60-yard scamper, and a 15-yard pass reception.

His “only real goof of the season” came against Lynn Classical, which Lowell lost 6-0. “Had I not dropped that damned pass with my slippery idiot fingers at the goal line, a pass from Kelakis straight and true into my hands, we might have won or tied. I’ve never gotten over the guilt of dropping that pass.”

On Thanksgiving Lowell hosted Lawrence and Kerouac scored the game’s only touchdown. In short order the Kerouac household was visited by Leahy, and later, Lou Little. Jack knew then that his dream of college was assured.

Part III

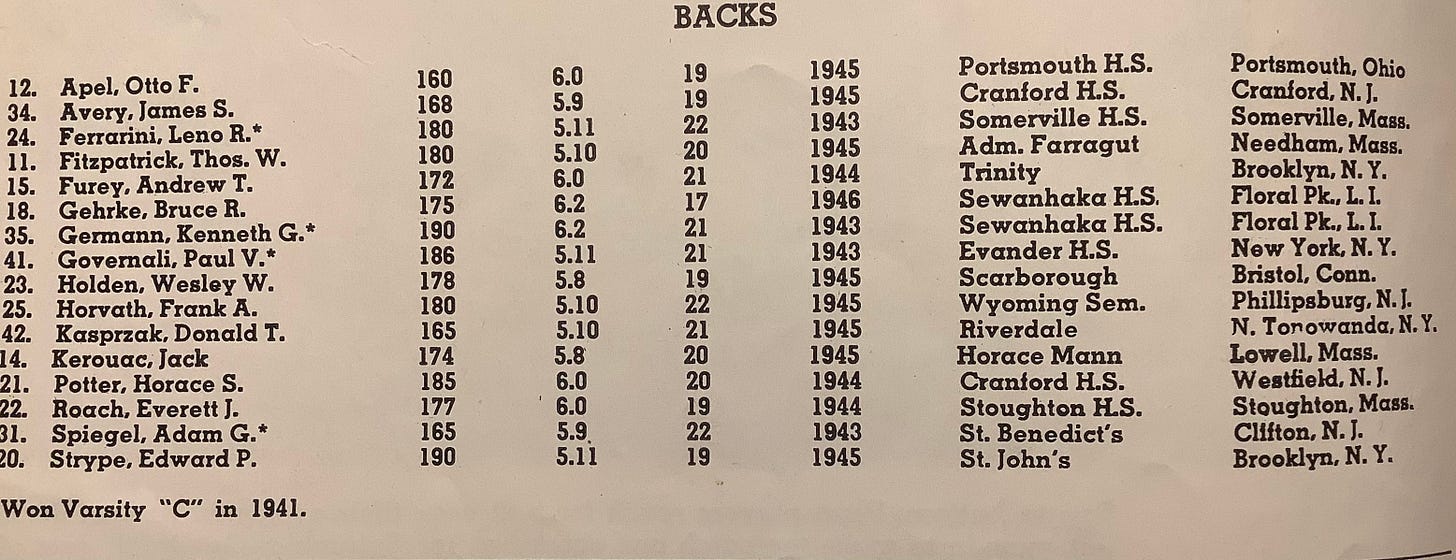

Leo, Jack’s father, wanted him to play for Leahy at Boston College,2 while Gabrielle, insisted her son go to Columbia. Mom won the argument, but Little insisted he attend one year of prep school at Horace Mann School for Boys in the Bronx to make up academic credits before enrolling at Columbia.

At Horace Mann, Jack progressed in both academics and football, even learning a new gridiron skill: the quick kick, which he executed successfully often during the season. In addition, he carried the ball, threw passes, and played defensive safety. “For the first time in my official football career,” he recalled, “a coach let me play every minute of every game in exactly the manner I was born to play.”

On to Columbia, Fall 1940

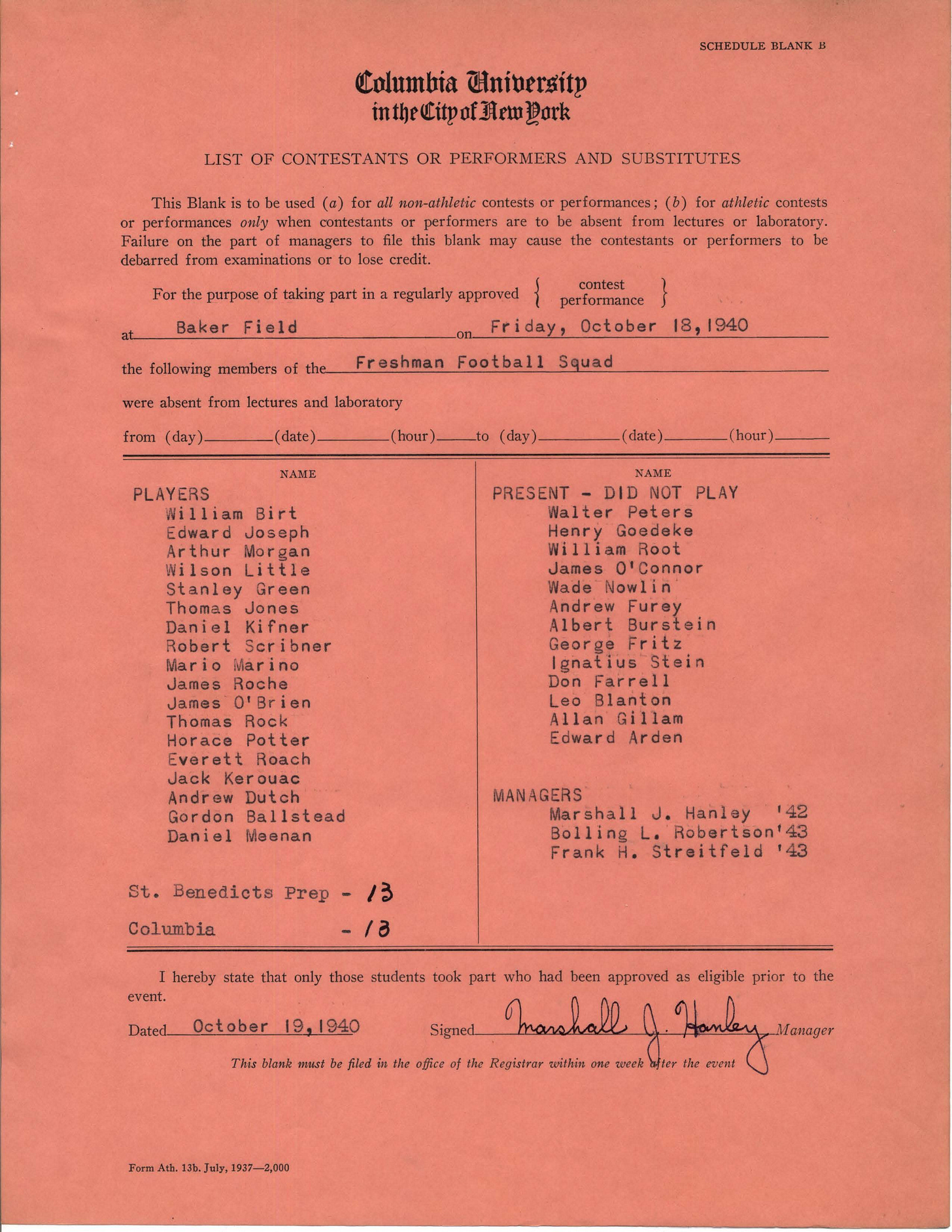

Jack was excited to be a college student and the opportunity presented to him on and off the field. As was the standard at the time, the school fielded a freshman team. Very early in the season, in the game versus St. Benedict, Jack suffered a broken leg.

He was finished for the season, yes, but he was broken in other ways. It injured not only his body, but his spirit, and though he continued at Columbia for a while, he eventually left school, held various jobs, including a short time as sports writer for his hometown newspaper, tried to enlist as a Navy pilot, and eventually became a merchant marine.

The summer of 1942 Jack was a merchant marine on the SS Dorchester3 as it transported supplies to England in support of the war effort. On the return trip, on September 26, he wrote from Nova Scotia to his childhood friend Sebastian Sampas telling him he’d be home soon with a week’s leave after which he intended to grab another seabound assignment. However, when he arrived home in October, he was surprised and pleased to find a telegram from Lou Little offering to make arrangements for Jack to return to Columbia.

He accepted Coach Little’s offer and returned to campus a few days before the fourth game of the season, the October 17th home game versus Army.

“Back I went,” he wrote, “finding myself in a Baker Field scrimmage no less than 48 hours after debarking the SS Dorchester. That Saturday. I played a few minutes in the Army game and decided to stop the sport for good.” [ix]

His pigskin-toting days were over.

Whether he told Little of his decision at once is not known. His name appeared on the official roster in the gameday programs each of the next three games— Pennsylvania, Cornell, and Colgate, before being removed.

In November he wrote to Sampas, “I am not sorry for having returned to Columbia for I have experienced one terrific month here. I had a gay, magnificent time of it.” [x]

He would drop out of Columbia a second time, but remain living in the area where he would eventually meet Ginsberg, Burroughs, and others.

In the early 1950s, while working in California as a brakeman for the Southern Pacific line, he was late to catch a train for his assignment. In Lonesome Traveler he wrote, “I run to it fast as I can go and dodge people ala Columbia halfback and cut into track fast as off-tackle where you carry the ball with you to the left and feint with neck and head and push of ball as tho you’re gonna throw yourself all out to fly around that left end and everybody psychologically chuffs with you that way and suddenly you contract and you like a whiff of smoke are buried in the hole in tackle, cutback play, you’re flying in the hole almost before you yourself know it, flying onto the track I am and there’s the train about 30 yards away even as I look picking up tremendous momentum the kind of momentum I would have been able to catch if I’d looked a second earlier—but I run, I know I can catch it.” [xi]

He did not catch the train—his athleticism was waning, his gridiron glory days far behind—but, like a train, fame was barreling down the tracks in his direction—and this oncoming freight without brakes he could not dodge.

[i] Early Writings, (The Sea), 167.

[ii] Vanity of Duluoz, 250.

[iii] Ibid., 15.

[iv] Ibid., 10-11.

[v] Ibid., 15.

[vi] Ibid., 11.

[vii] This and all Kerouac quotes from Vanity of Duluoz, 15-19.

[viii] Lowell Daily Sun, October 10, 1938.

[ix] Atop an Underwood, 179-180. Note: Not only was he disappointed in his lack of playing time, but the story of Little’s promise to get Leo a job in New York surfaces here again. See footnote 1 below.

[x] Early Writings, (The Sea), 321-322.

[xi] Lonesome Traveler, 51.